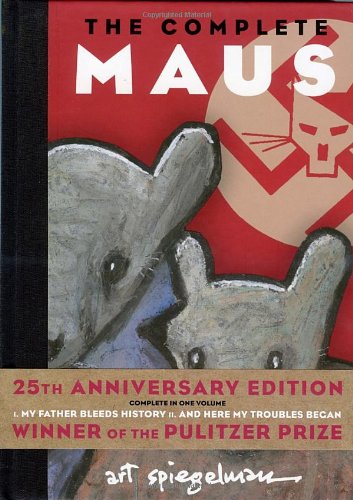

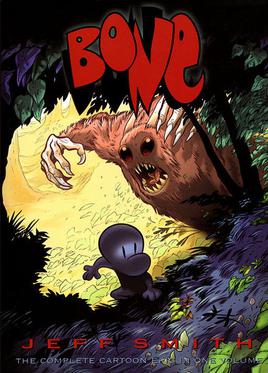

Perhaps it is because of the stereotype that comics are meant for children, or perhaps it is because violence and sex scenes are 'more shocking' when depicted through illustrations instead of words.

"Graphic novels

that do contain violence or sexual content are generally labeled as 'adult,' and...using

the term 'adult' in relation to graphic novels is often taken to mean the novel contains pornographic

content. While some graphic novels do contain sexual content, the label 'adult' does not mean

pornographic, it may be in reference to philosophical and emotional content that targets a more mature

audience."

--Janet Pinkley & Kaela Casey, 2013

|

| Cover of Saga #12, the issue in question. The offending images were drawn within the screen of character Prince Robot IV. |

And that is the issue with censorship, in graphic novels and all other cases. Challenges are arbitrary and so are the judgments on whether or not to allow publication or to keep on the shelves. In 2014, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) teamed up with the Banned Books Week committee to shed a light specifically on graphic novels. One such graphic novels, listed on CBLDF's website, is Neil Gaiman's Sandman. Citing reasons such as "anti-family themes", "offensive language", and "unfit for age group", Sandman has been challenged at numerous libraries across the country since its publication in 1989.

Sandman's example may serve to back up the advice Pinkley and Casey give in their writing...each graphic novel's audience must be assessed individually and shelved appropriately, rather than assuming it is meant for a younger crowd. But no matter the age, all graphic novels should be treated as proper literature, and as potential gateways for reluctant readers.

Resources

- Pinkley, Janet and Kaela Casey. (2013) "Graphic Novels: A Brief History and Overview for Library Managers." Library Leadership and Management, vol. 27, iss. 3, pg. 1-10. Accessed online at http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/ehost/detail/detail?sid=abbcca04-628f-4974-8235-1ae730e89940%40sessionmgr4005&vid=2&hid=4106&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=lls&AN=90590321

- Dooley, Michael. (2014) "An Uncensored Look at Banned Comics." Print, vol. 68, iss. 1, pg. 48-59. Accessed online at http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/ehost/detail/detail?sid=b63d9711-7d56-4dda-a7f3-fcb5f961739b%40sessionmgr4002&vid=5&hid=4106&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=94084847

- Sacks, Ethan. (2013) "'Saga' comic book issue temporarily banned from Apple app over 'postage stamp-sized' graphic gay sex images." New York Daily News, accessed online at http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/music-arts/comic-book-temporarily-banned-app-gay-sex-images-article-1.1313196

- Volin, Eva. (2014) "Celebrate Banned Books Week with Graphic Novels." Booklist, vol. 111, iss. 1, pg. 92. Accessed online at http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/ehost/detail/detail?sid=d6139bf5-bfe4-42c5-bebf-787c7200d4de%40sessionmgr4002&vid=3&hid=4106&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=lls&AN=97828685

- http://cbldf.org/, official website for Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. You can find their case study on Sandman at http://cbldf.org/banned-comic/banned-challenged-comics/case-study-sandman/